In the following post, PhD student in sociology Jessica Yorks, discusses the challenges–and assets– first-generations bring to higher education. Based on her personal experiences and conversations with others, she offers advice on how instructors can better support first-generation students while recognizing the value of the perspectives they bring to higher education.

For many of us, our parents are our biggest supporters in college. They buy us brand new bed sets and decorations for our dormrooms, they take us out to eat when they’re in town, they send us money when we need some, and they help us with our assignments when we need guidance. But what about the students whose parents don’t understand the higher education system because they never attended college? Known as first-generation students, this group of students often face a host of challenges in college because their parents aren’t able to be there for them in the ways that many other students’ parents are. As the first in their families to attend a postsecondary school, first-generation students likely have to navigate the college world themselves. Unfortunately, this often means that they struggle more and have worse academic outcomes. For example, research shows that first-generation students, compared to those with college-educated parents, are four times more likely to leave college (Engle & Tinto, 2008) and are 51% less likely to get a degree in four years (Ishitani, 2006). Studies also show that only 24% of first-generation students obtain a Bachelor’s degree within eight years (Chen & Carroll, 2005). These sobering statistics beg the questions:

What is going on with first-generation students that they have poor academic outcomes? How can college faculty, graduate students, and academic support staff address their unique needs?

To answer the first question, it’s important to consider the many struggles these students face trying to get a college education. I am a first-generation student and have personally experienced many of these issues during my time as a student. In this post, I will discuss some of my own personal experiences with this topic as well as fellow first-generation students’ thoughts about the challenges they’ve had. Overwhelmingly, many first-generation students report one of the biggest challenges they face is a general lack of information about how to do well in college. This problem can range from mundane issues like how to dress and how to write emails to more serious problems like how to change your major and how to seek help related to a poor test grade. For many students whose parents have gone to college, they are able to discuss their issues with their parents who can provide guidance. Unfortunately for many first-generation students, they must figure out the issues themselves, which often means they have more challenges along the way.

Another issue that many first-generation students struggle with is the fact that they must straddle two worlds. Because their families don’t understand the higher education system, these students feel like they don’t fully belong at home; however, the opposite is true in that the higher education system doesn’t fit with their personal experiences at home, so first-generation students often feel out of place in both worlds.

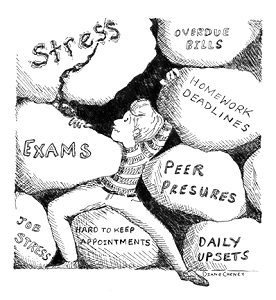

This tension, of course, means that many first-generation students feel like imposters in school and that they weren’t cut out for college (even though that’s not true). In addition, many first-generation students have to deal with outside demands such as family issues and work obligations. This is particularly true for first-generation students with fewer resources to help mitigate some of these demands. These students may struggle to keep up in classes or have issues come up that prevent them from coming to class or finishing assignments on time, which can be very difficult to manage.

First-generation students often also lack adequate academic guidance and emotional mentoring, both of which are essential to doing well in school. Because these students often cannot call home and get help from their parents when dealing with academic-related problems, first-generation students are likely to try to figure out academic things on their own or find support on campus through faculty and staff. Also, many of these students often need more mentoring on a personal level because they’re trying to get through a system that doesn’t address their unique needs.

So, what can we do to support first-generation students? As a first-generation student, I’ve asked this question myself and talked with fellow first-generation students about this question many times. Based on my thoughts about this question and countless conversations, below is a bulleted list that outlines a number of ways faculty and staff can help first-generation students adapt to college life.

- Make explicit the ‘hidden’ curriculum of higher education. By this, I mean to expose students to all those things we don’t talk about: what office hours mean, how to read quickly for content, how to find and cite research, and how to organize and balance their time. The more we can make all those taken-for-granted pieces of knowledge explicit, the better first-generation students can navigate college. In my writing classes, I offer tutorials for students to learn the science of finding, reading, and citing research for their papers. .

- Build their social and cultural capital. Social theorist Pierre Bourdieu discussed cultural capital as cultural skills and knowledge and social capital as the investments in social relationships and networks. According to Bourdieu, utilizing these non-financial forms of capital can help individuals get ahead in life (Bourdieu & Passeron 1977). Thus, we should help first-generation students build their cultural and social capital. A way to encourage cultural capital is to increase their knowledge of the university culture, such as how to write a research question.

A way to build social capital is to foster relationships and team building between students by providing ample opportunities for them to talk and share their experiences. From my own experience, developing peer relationships inside the classroom was absolutely pivotal to my persistence in college. Through opportunities to build social capital and get to know others like myself, I felt more like I belonged in college and had a support system to help me get through the unique challenges I faced as a first-generation student.

- Find other ways to hear first-generation students’ voices . Because many first-generation students feel like they don’t belong in school, they are more likely than their peers to hold back and not participate in class. Creating opportunities for them to share their voices, such as through individual meetings, papers, or peer discussions is another great way to engage first-generation students in the classroom.

- Be aware of your own background, biases, and experiences and how they may shape your interactions with first-generation students.

Those of us in academia can easily take our specialized knowledge for granted and judge others who do not adhere to the same rules we’re used to. For example, first-generation students who send emails that aren’t professional may seem rude or careless but we should not be so quick to judge. Their lack of crafting emails in a particular way doesn’t automatically mean they don’t care about professionalism. These students simply may not know how to construct an email or the importance of doing so. Often, these students just need some guidance about how academia works instead of being held to the high standards we construct for ourselves.

- Understand their life situations. Many first-generations deal with issues outside of academia and need more emotional support from faculty and staff who can understand why they needed to miss class or why they’re asking for an extension on their paper. It’s not that these students don’t want to do well in school but family obligations and work (among other things) are very real concerns for them that may impact their studies. Having professors who would take these issues into account was super important for me as a first-generation student because I had a lot of work and family demands and their support enabled me to juggle issues that would come up. Not having this understanding from faculty would have made college much more difficult, if not impossible, for me.

- Be aware of and provide students with on-campus resources – do some research! What programs are there for first-generation students? Would the cultural centers provide a sense of community for them? Is there a commuter group that they might benefit from? Do they have a Student Support Services (SSS) program specifically designed for first-generation students? (UConn does: https://cap.uconn.edu/sss/summer-program/) How can you connect them with opportunities on campus to help them succeed?

- Identify yourself as a first-generation student – if you were the first in your family to attend college, let your students know. You can provide insight into your own challenges at school and how you overcame them to get to where you are today. First-generation students then also know that they could rely on you as a resource to help them figure out the confusing world of college.

Although first-generation students bring many challenges to college, it’s important to note that they have many strengths as well. Many of these students are often very serious with their school work because they know how much of a privilege it is to attend college. They radiate a certain authenticity about wanting to be in school and do well rather than just being there because it’s expected of them. They’re also very resourceful and strategic in finding ways to do well in school. And, importantly, they bring new and important insights and perspectives into the classroom by sharing their own unique experiences. This practice is great for increasing diversity and inclusion in the classroom, which is a worthwhile goal for those interested in social justice issues (hopefully all of us). Ultimately, their differences can act as their strengths as well.

We must find ways to engage first-generation students and encourage them, not push them out of college. Many of them are working hard to be in school even though they’re facing many challenges and they deserve an opportunity to get through it. As teachers and mentors, we need to be attuned to the particular issues that first-generation students face so that we can address them and help these students feel supported and successfully navigate college life.